Feb 7, 2017

Recognizing Personal Bias

It was the mid-1960s and a young Chicano man from New Mexico was sitting on a bus in Chicago on his way back home after work. As the bus drove through the city’s different neighborhoods the demographics of the people changed. Eventually, the young man realized he was the only person on the bus who wasn’t African-American and he immediately felt fear.

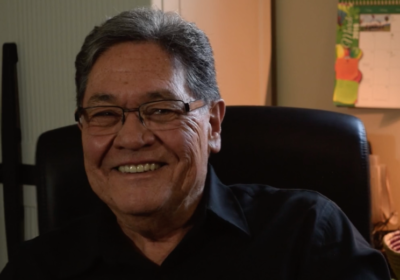

It was during this bus ride that Roberto Chene, a now nationally recognized consultant in intercultural communication and conflict resolution, realized for the first time his own biases and prejudices.

Chene is well-known around the country for his unique approach to intercultural communication trainings that help dismantle racism by creating a safe space where people can openly talk about how racism, colonization and historical trauma have impacted their lives. This leads to a deeper conversation of what racial equity is and how it can be incorporated into the structure of organizations.

“We learn to be afraid of each other and we learn to be biased,” Chene said. “You can’t control that you become infected with prejudice. It happens in a society that is so dysfunctional and biased like ours.” While the bus ride was a defining moment for Chene, it is just a small part of his story. It helped Chene deepen his self awareness in order to create his distinct facilitation method. The rest is a journey of family, faith and community.

Rooted in Community

Chene spent the first four years of his life in Dawson, a close-knit community in the northern part of the state. “I grew up in your traditional Chicano, Hispano family here in New Mexico,” he said. Chene credits his upbringing in Dawson as the foundation for his commitment to building community. “The validation of community has somehow become a metaphor for everything that I care about,” Chene said.

Every year, Dawson holds a community picnic and the families who once lived there come back to reconnect. “So the subsequent generations going back to 1950 come back,” Chene said. “It’s what community is and should be and continues to be to a great many people.” He’s spent his life trying to recreate that deep sense of community in Albuquerque. Becoming a Learner After the mine, which was the major employer of Dawson, closed his family moved to Santa Fe and later to Albuquerque. Growing up, Chene’s family had a strong connection to the Catholic Church. For the majority of his primary and secondary education, he attended Catholic schools in Albuquerque.

When he graduated from St. Mary’s High School in 1963, he went to the University of New Mexico and studied sociology. As an undergraduate, he became involved with the Newman Center, which provides religious and social support to Catholic students. This is where he made all his friends and it became a centerpiece for his time at UNM. Nearly a decade later, he would marry his wife, Connie Chene, at the Newman Center. In his second year at the university, the Dominican Order of the Catholic Church offered him the opportunity to serve as a social worker in Chicago, Illinois. “It sounded exciting, an adventure and I had never really been out of New Mexico,” Chene said. “So, myself and some other guys we got in a car and drove to Chicago.”

At the end of the summer, a priest from the Dominican Order asked if he was interested in joining the order. “I had never thought about that, but then his question got me started thinking,” said Chene. “I think my interest in all of that fit. So, I decided when I got back to actually enter the Dominican Order.” In 1965, Chene left New Mexico to begin a year of relative solitude at a monastery in rural northern Minnesota. Then, he began taking classes at the Dominican University in River Forest, Illinois, where he earned his undergraduate degree in philosophy. It was in these classes that he questioned his own existence and purpose. In the search for answers, Chene realized he was a thinker– in a deep and meaningful way. “I realized at some point in my study that I was a philosopher, that I could think for myself,” he said. “I think that it affected how I felt about learning. So, I became a student in the sense of being a lifelong learner.” He described this moment of self realization as life-changing and its impact is felt to this day. He still thinks of himself as philosopher, learner and deep thinker.

Meeting Connie

In the late 1960s, Chene had the opportunity to study liberation theology, which according to the Oxford Dictionary is “a movement in Christian theology, which attempts to address the problems of poverty and social injustice.” He was studying from Ivan Illich, a former priest turned radical theologian spokesperson, at an institute in Cuernavaca, Mexico. He met his wife Connie during a break from Sunday mass on the plasticas outside the cathedral. Connie was a nun, living in Cuernavaca to study Spanish.

She has just arrived in Mexico with the other sisters and they were looking for a place to stay. Chene, who knew some of the other nuns, suggested they try to get an apartment at Las Rosas Bungalows where he and the other seminarians would be living. Over the summer, Chene and Connie became really good friends. “Whenever we had time, we talked about our commitment to celibacy and our commitment to religious life.” Eventually they both left Cuernavaca to rejoin their religious orders in the United States. However, they stayed in touch by writing letters.

Over the next few years, the pair would write each other almost every day. “The letters got more and more personal,” Connie said. This romance led to a trip to the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore in the summer of 1971. While walking the sand dunes, they acknowledged their feelings for one another. “It really dawned on me how much I really, really loved her,” Chene said. “But we had respective commitments.” By the winter of that year, Connie had decided to leave the convent. She called Chene and told him “this relationship you and I have is telling me that I want something else in my life.” Connie ended the call by telling Chene she would see him at ordination in May of 1972. Two months before he was to be ordained a priest, Chene left the Dominican Order to be with Connie. They’ve been married for 43 years.

Becoming a Father In Albuquerque, the Chenes started a family. It was with the birth of his first child and only daughter Ana Chene that he would confront the balance of family and work life, and his own male privilege. “I became addicted to work,” Chene said. “The fear of failure to not make a living for me and my family became a driving force.” He said this work addiction was linked to our society’s standards that men are the providers of a family. This way only intensified after the birth of his second child, David Chene. ” I fell victim to this problem even though both of us were working. Connie as a teacher and eventually a principal. I was a social worker and mental health therapist,” said Chene.

Not only was he dealing with the stress of trying to provide for his new family but with the help of his wife Connie, other women friends, as well as men’s support groups, Chene learned about male privilege and sexism and how it harms women and families in our society. Each of these moments combined to create the anti-oppression values and practices Chene uses when working with organizations that have chosen to create a more equitable environment for their employees and the work they engage in. One youth participant in Chene’s training said “I learned a lot about the way different groups contain the traumas of their history. Terms like ‘recruit and abandon’ and ‘historical anger vs. historical guilt’ allowed me to explore the ways it affects me.” She continued on to say “my takeaway from this training is how important healing is, and also the way to understand and observe my thoughts in order to spread love.”

Today, Chene is a consultant with local non-profits and national foundations to ensure New Mexico’s history of colonization, genocide and historical trauma are recognized when institutions engage in racial equity work in this state. He has dedicated his life to making sure people across the nation are heard and critically understood from a racial equity, decolonized lens. Chene’s facilitation of healing has had an immeasurable impact on the community.